bthbib

Lena Sandin Wranker MD

School of Health Science, Blekinge Institute of Technology

School of Health Sciences, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Lund University

Peter Anderberg Tekn Dr

School of Health Science

Blekinge Institute of Technology

Abstract – The number of researchers among medical doctors has declined. How to recruit researchers has become a problem internationally. It is an obvious risk that a strained financial situation will result in fewer resources to education and research. There is a lack of understanding of how to break this negative trend. Knowledge about what is promoting and what is hindering students to clinical research and education is lacking. This pilot study investigates issues related to research among one group of younger medical doctors taking a university course in research methodology and another group taking a professional development course in basic scientific education.

The aim of this study was to analyze factors that either promotes or constitutes an obstacle in medical doctors’ choice between two levels of education. The first level was a shorter course in basic scientific education, (FoUST), resulting in a certificate. The alternative given was a course in research methodology, (FoU), resulting in 30 credits at Lund University. This study will focus on attitudes towards research and results will be implemented in future courses, in an attempt to make them more relevant for both students and clinicians, regarding content and pedagogy.

Method: An established questionnaire, formerly used to study attitudes among medical students at Karolinska Institutet, was used. The questionnaire was expanded with questions concerning attitudes to local research. Participants in this survey were gathered from the Centre of Competence, Blekinge Hospital in Karlskrona (N=18). All doctors attending the courses given during autumn 2011 were included.

Result: The median age of the population was 33 years. The majority, 4/6 (67%), in the FoUST-group expressed that research should be conducted at Blekinge Hospital. The majority in the FoUST- group, 5/7 (71%), also thought that their working conditions will admit research. A quarter, 2/7 (24%), thought that research involvement could be needed in the future in order to keep intellectual stimulation. In the FoU-group, 11/11 (100%), expressed that research should be conducted at Blekinge Hospital, but only a quarter 3/11 (27%) thought that the working conditions gave opportunities to combine ordinary work with research. Research, as intellectual stimulation, was reported as important by the majority 8/11 (70%).

Conclusion: The attitude to local research at the Blekinge Hospital is positive among students. The groups differ according to whether research is needed to get intellectual stimulation. A course, which to a higher extent integrates research and clinical work, is needed. Future research needs to highlight alternative ways where education and clinical work will become more integrated. A deeper analysis, of differences in working conditions and estimated possibilities to conduct research, is needed among medical doctors at the Blekinge Hospital, Karlskrona, Sweden.

Keywords – attitudes, scientific education, research, medical doctors

1. Introduction

Internationally, the number of researchers among medical doctors has declined (1). In Canada, economical rewarding systems have been introduced and in the United States of America proposals to facilitate for young researchers have been forwarded (2, 3). Australia has tried to recruit young students to postgraduate education, as with research combined with working as trainee to get clinical skills (4). Researchers have shown a lack of understanding among students for the necessity to integrate new findings into the clinical work (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). A lack of awareness of what kind of research activity teachers and mentors are involved in has also been demonstrated (5, 6, 9).

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) and proven experience should be the guiding principle in doctors’ lifelong learning (11). The Bologna process has meant that formal scientific elements have been increased in both the theoretical and the practical everyday life (7). As a result of this, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, (SoS), have issued new regulations and guidelines on doctors’ specialist training (12). This is a framework system in which the local health authority then has the task to design the education. This means that there are differences, already, between how our medical faculties design their curricula. With a strained financial situation, there is a risk of shrinking resources assigned to the theoretical scientific basis of training and scientific work under supervision. The Swedish Society for Surgery has acted to formulate goals for the specialist service (13).

In 1989, extended training in research, for general practitioners, was introduced in the southern healthcare region of Sweden (14). This FoU course has a long tradition and has been offered for more than 20 years in Blekinge county council and is a preparation course for researchers (FoU) awarding 30 credits. For most of the students the value is a greater understanding for research but for some it is the beginning of the education to become a researcher. The course is tailored according to the Bologna process. The courses have been evaluated and are nowadays offered to several categories of staff in the health care organization, and are expected to do some good for the clinics (15). The course is offered in several locations in the southern healthcare region, of which Blekinge Hospital is one. Locally, there are course managements dealing with the administration of the course while examination responsibility rests with the Department of Community Medicine, Lund University.

The new regulations and general advice regarding medical specialist training, from SoS, means that training physicians must be able to verify scientific skills to apply for accreditation as a specialist (12). In the Blekinge county council, a short course has been established (FoUST). This course met the requirement that all ST doctors should have a scientific method course, a 20 days course in basic scientific skills no credits. The FoUST, given at BLS, has been arranged by the principal agency and is now executed for the second time at the Centre of Competence at Blekinge hospital. The basic training in the scientific approach is the main reason for giving the course but the recruitment of future scientists must also be considered. County councils have, by law, a responsibility, not only for the clinical work but also for clinical research (16). This is the framework within which the health care provider has the task to put it into practical use by creating curriculum for the specialist training. The FoUST course has been developed for those who, at least initially, do not have any real interest in research, but attend the course as an obligatory part of their medical education.

These two courses are not coordinated and there are no possibilities to change from one to the other. The FoUST course cannot be credited as part of the FoU course. The scientific advisory board at Blekinge county council has noted this and given the responsible course directors the task to investigate the possibilities to coordinate and if possible integrate the two courses. The task implies looking through the curriculum, the objectives of the course and the pedagogic strategy for the FoU course. The aim is to certify that the course meets the requirements set up by academia as a foundation for continued research studies as well as the demands from the health care provider, i.e. the formal requirements to pass the ST education. As Anderberg and Forsell showed in their examination paper in the basic pedagogy course 2011, the FoU course needs to be thoroughly revised and modernized (17). It is equally important that the course is recognized as relevant for the students as part of their professional development (18, 19, 20). The context in which this work is being processed will be a university education which supports the development of competence of professionals in their life-long education and learning (21, 22).

The question of how universities and university education can support the societal and individual need for lifelong learning and continuous education in medicine is becoming increasingly important (26, 27, 28). An important subject is the need for formal or informal revalidation of professional knowledge in the ever changing research front of medicine and corresponding need for the physician to incorporate new research results into clinical practice (29). In the case of medical education there is a “shift towards lifelong learning which emphasizes the need for physicians in practice to be comfortable with continuing education long after they pass their certification exams as well as with corresponding assessments of knowledge, skills, and attitudes throughout their careers” (27). The incentive to change the education in this direction is of much concern and debate and a lot of research is undertaken but with relatively few solutions to how it should be done (27).

In order to reverse the negative trend of fewer and fewer doctors researching, there is an obvious need of knowledge both about the motives that attract doctors to graduate, and about what prevents them from doing this. The scientific approach is an undeniable element of the whole also for clinicians. Skills in EBM, as well as how these skills should be applied in the everyday clinical use, are key factors in helping students developing their scientific and clinical expertise (23, 24).

The aims of the present study were to investigate factors assumed to influence the choice between a career as researcher or clinician among medical doctors. The study analyzes the motives of doctors for selecting the short course (FoUST), that leads to a certificate of academic skills, or for choosing the longer, 30 credits, research methodology course (FoU). The study will focus on attitudes to research and to put this into the context of lifelong learning.

2. Method

2.1 Sample

Information on attitudes was obtained by using the questionnaire that formerly has been used in a Swedish study of medical students and resident physicians associated with Karolinska Institutet, Sweden (25). This questionnaire, supplemented with questions concerning attitudes to research locally, (Appendix 1), has been used to study the attitudes of the physicians and trainee physicians, who are now attending the 30 credit course in research methodology (FoU), or conducting a course in science proficiency (FoUST), at the Center of Competence, Hospital of Blekinge.

Participants in the present survey were recruited among students at the Center of Competence, Blekinge Hospital. A total of 18 physicians studying either the basic science (FoUST) course 7/7 (100%), or 30 credits research methodologies (FoU), 11/11 (100%), accepted participation.

2.2 Procedure

Potential participants were orally invited to participate in the study. The questionnaire was distributed at a seminar to participants in the group studying scientific skills (FoUST). Participants in the course (FoU) were given the questionnaire during a lesson. The questionnaire was answered in connection with their regular meeting and was completed in thirty minutes.

All data in this study is drawn from the survey.

2.3 Measures

Age, sex, planned specialty and estimated student debt data was collected from the questionnaire.

The work situation was answered through the question: Do you think it may be possible for you to do research as your work situation looks like today? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Attitudes to research were addressed by the questions:

– What would you most like to do in five years?

– Has your interest in research increased or decreased during basic training? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ and with options for open answers.

– Has your interest in research increased or decreased during your clinical service ? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ and with options for open answers.

– Do you think that a credits course could improve your ability to take up new scientific capabilities and thus be better as a clinician? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Future research was addressed by the questions:

-Are there any reasons that made you a researcher or to suggest that you are going to invest in research in the future? Please rank the three most important reasons from 1-3 where 1 = most important. The response alternatives were intellectual stimulation, career, knowledge, free working hours, variation in work, easier to combine with family life, travelling, developing health care, low stress, other factors.

-Why did you not got involved in research ? Please rank the three most important reasons from 1-3 where 1 = most important. The response alternatives were economy and wages, low status, increased workload, divisive, difficult to combine with family life, want to work in practice, want to decide over my time, lack of interest for research, and other reasons.

Financial incentives were addressed by the questions:

Do you think the ability to deduct your student loan if you choose a research career (> 30% of the time) could affect / have affected your decision to invest in research in the future ? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Do you think guaranteed wages during a possible research career (> 30% of the time) like wages clinicians have could influence / have influenced your decision to invest in research in the future ? The response alternatives were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

EBM was addressed by the questions:

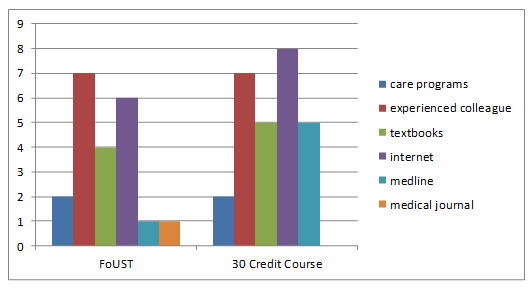

How do you obtain new scientific knowledge / trying to solve difficult clinical cases? The response alternatives available for the ranking were care programs, experienced colleague, textbooks, internet, Medline, medical journal. Possibilities of free-form responses were given.

How many scientific papers (not medical journal) do you read per year? Free-form responses were given.

2.4 Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the data from the investigation of attitudes. As data was not considered normally distributed, the Spearman´s chi-square test was used in order to control for differences between the groups. To compare the age-distribution in the groups, an independent t-test was used. All analyses were carried out using the SPSS program, version 17.0. The probability values (p-value) revealed statistically significant results. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Missing data is indicated by (N) in all analyses.

3. Results

The medium age of the participating students was 33 years (min. 29, max, 39). Of the respondents, N=18, 88% (N=15) were ST physicians. The minority were women 6/18 compared with men 12/18. The majority had a Swedish medical exam 16/18 (89%).

The male group evaluated that they were capable of critical reading of scientific articles 5/8 (62%). The comparing figures for the female group were 3/6 (50%). By participating in either of the courses, the expectation to be able to critically scrutinize articles increased in both groups totally 10/13 (77%). When finding solutions to professional problems, the majority of the course participants indicated that the first choice was to ask more experienced colleagues, followed by using the internet or professional literature. Female doctors 6/6 (100%) thought they would be able to participate in the 30 credits FoU course. The corresponding figures among the male doctors were 9/11 (82%). The female doctors 3/6 (50%) thought that the work load in daily work allowed research. The corresponding figures among the male doctors were 5/11 (46%). The whole group of female doctors 6/6 (100%) and 8/10 (80%) of the male doctors think that research ought to be carried out at the Blekinge Hospital.

On the question “how important is it that research is carried out at Blekinge Hospital (0-100)”, the estimated medium value was 67 with std 23 (N=16).

Intellectual stimulation was the most important argument for a future as a researcher among physicians in the 30 credit course. Varied work followed by intellectual stimulation was the main argument in the FoUST. Economy was the most important argument for not choosing a future as a researcher among physicians in the 30 credit course. A fragmented work situation was the main argument in the FoUST together with feelings of work overload.

The size of the study debt was 160.268 SKr among students in the FoUST-group) compared to 265.545 in the FoU-group. Both groups had one student without study debt.

The outcome of students who consider a secured salary growth important for an eventual research career does not show any certified difference between the two groups. In the FoUST group, 2/7 (29%) thought that a certified salary growth is important, 4/7 (57%) that it is not important, while 1/7 (14%) did not answer the question. In the FOU group, 5/11 (45%) consider the salary growth as important while 6/11 (55%) did not find it important. The outfall of students who consider a secured salary growth important for an eventual research career does not show any certified difference between the two groups. In the FoUST group, 2/7 (29%) thought that a certified salary growth is important, 4/7 (57%) that it is not important, while 1/7 (14%) did not answer the question. In the FOU group, 5/11 (45%) consider the salary growth as important while 6/11 (55%) did not find it important.

In the FoUST group, 2/7 (29%) considered that tax reduction based on study dept would stimulate the interest for research in a positive way while 4/7 (57%) did not believe that it would stimulate their interest for research. In the FOU group, 5/11 (45%) thought that tax reduction would stimulate the interest for research, while 6/11 (55%) did not think it would make any difference.

In both groups, 8/18 (44%) believe that the work load would admit research. In the FoUST group, 5/7 (71%) believed that the work load would admit research. Comments from those who did not believe so are: “Need to have more time allocated”, “(research) would negatively influence on clinical practice”. In the FOU group, 3/11 (27%) believed that the work load would admit research. The comments that explain why 8/11 (73%) did not believe that the work load would admit research were: “Negative influence on clinical duty”, “hire more doctors”, “more time, more resources as research nurse, secretary to keep the registers, “too high work load, too few doctors”,” lack of tutors”.

The majority had a low interest in research during medical training. Example of comments: “Experienced few good role models during medical training”. “People with total focus on details”. “Much lonely work”, “Desk work”. “Chose the medical profession to carry out clinical work”.

When solving problems, the majority of the Foust course consult older more experienced colleagues in the first place, closely followed by searching on the internet or textbooks. In the 30 credit course, internet was used as the first choice followed by asking a more experienced colleague. A big difference between the groups is the use of Medline. Fig 1.

Fig 1. Use of resources in problem solving among students in the FoUST and 30 credits course.

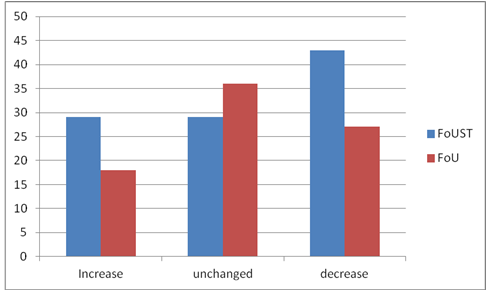

The majority of physicians in both groups could not report an increasing interest for research during their clinical duty.

Fig 2 Development of interest for research during clinical duty

(1 in the FOU group did not answer)

Example of comments:

“Few role models. One already uses a lot of time to fill in quality registers etc”.

“You have not time for everything. I have other professional interests”.

“There is already too much I ought to read and get into”.

“Too many details. I like the broader picture”.

“On a smaller hospital…., it is vital to get economical resources again and again”.

“The distance to the university prevents me”.

“I work in the countryside. We are too few doctors for the population we serve”.

“It would be more tempting with an alternative to the clinic”.

4. Discussion

The aim of this pilot study is to investigate self- reported factors and attitudes pro or con scientific research among the medical doctors at the Blekinge Hospital. In the longer term, the expectation is to be able to offer education which meets the demands of the medical doctors (and the organization), both in regard to contents and possibilities. The theoretical foundation is lifelong learning in higher education. At the Blekinge Hospital, there is an ongoing work to revise curriculum and number of preparation course for researchers (FoU). Blekinge Institute of Technology is participating in this work the School of Health Science.

An analysis of the answers shows that medical students realize the need for research and think that it is vital that research is carried out on the local level. Despite this, the majority of doctors undergoing training do not show any interest for an academic career and it is even regarded as an obstacle for becoming skilled clinicians. However, developing into a skilled clinician requires, besides clinical training, both a critical review of articles to follow the research front and to work according to evidence-based medicine.

Results from previous studies suggest the need to connect clinical research with basic training for doctors (5, 6, 13). The process leading up to the research needs to be clarified and opportunities to develop scientific skills in the form of project work in early education has been introduced after the general regulations and guidelines that the SoS gave out in 2008. This is likely to lead to changes in attitude to research and scientific work in the future.

Another important question is whether it is possible to assist clinical researchers in universities to present their findings faster and reconnect to basic education. Perhaps this would be facilitated by linking basic education to physicians closer to clinical research in our universities. In China, this need is also described as well as the need for dedicated mentors to support the research process among students (24).

A major difference between the study groups related to intellectual stimulation. For physicians in 30 credits course, 70% indicates that stimulation of the intellect is the ground for future research commitment compared with 24% among those who read Foust. One possible explanation may be that the training is so tight that there is no need for more intellectual stimulation. An analysis of the results nevertheless reveals that in the acquisition of knowledge in the first instance the consulting with older, more experienced colleagues or looking on the internet is used, while the use of Medline and articles on the subject are only marginally exploited. The risk is obvious that the requirements of EBM as the duty of every clinically active physician in the long term may be compromised if trust in the older literature is chosen over reliance on new findings.

The main finding of this study is precisely the need to create a course that integrates the two parts of research and clinical practice. The study supports the need to have a sufficient theoretical base to provide skills that allows one to move on to graduate research studies, but also to connect adequately to the clinical work to be relevant for those who do not have any ambitions to do research. They will then be “competent research consumers”.

A future major challenge for educators is to develop a methodology for skills development in the lifelong learning where a theoretical superstructure also attracts individuals with a long professional activity.

This study provides a topographic image of the need for a course in scientific approach or for a research preparation course. We are aware of the need to follow up these results with a more in-depth study in specific areas such as how teaching could be more closely linked to the clinical work. A qualitative interview study with some of the students could be a host complement.

5. References

1. Nielson EG. The role of medical school admissions committees in the decline of physician-scientists. J Clin Invest 2003;111:765-767

2. Lander B, Hanley GE, Atkinson-Grosjean J. Clinician-Scientist in Canada: Barriers to career entry and progress. Clinician-Scientists in Canada. PLoS ONE 2010. 5(10):e13168. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013168

3. Farrell GC. Career paths for clinical scientists. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11(9):891-894

4. Burgoyne LN, O´Flynn S, Boylan GB. Undergraduate medical research: the student perspective. Med Educ Online. 2010 Sep 10;15. doi:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5212

5. Hren D, Lukic´ IK, Marusic´ A, Vodopivec I, Vujaklija A, Hrabak M, Marusic´ M. Teaching research methodology in medical schools: students´attitudes towards and knowledge about science. Medical education 2004:38;81-86

6. Pruskil S, Burgwinkel P, Georg W, Keil T, Kiessling C. Medical students´attitudes towards science and involvement in research activities: a comparative study with students from a reformed and traditional curriculum. Med Teach 2009:31(6):e254-259.

7. Murdoch-Eaton D, Drewery S, Elton S, Emmerson C, Marshall M, Smith JA, Stark P, Whittle S. What do medical students understand by research and research skills? Identifying research opportunities within undergraduate projects. Med Teach 2010;32:e152-e160. doi:10.3109/01421591003657493

8. Schrier RW. Ensuring the survival of the clinician-scientist. Acad Med. 1997;72(7):589-594.

9. Restifo LL. Phelan GR. The cultural divide: exploring communication barriers between scientists and clinicians. Disease Models Mechanisms 2011:4;423-426. Doi:10.1242/dmm.008177

10. Boulter D. Public perception of science and associated general issues for the scientist. Phytochemistry 1999:50;1-7.

11. Littlewood S, Ypinazar V, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Dornan T. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ 2005:Vol 331:387-391.

12. Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om läkares specialiseringstjänstgöring. SOSFS 2008:17.

13. Haglund U, Frisk J, Ivarsson M, Naredi P, Lisa R. ST-utbildningen ska ge kompetens i medicinsk vetenskap. Kirurgföreningen föreslår en kursplan för alla ST-läkare. Läkartidningen 2008;105:369-372.

14. Håkansson A. Decentralicerad forskarutbildning. Lyckad kurs i Södra sjukvårdsregionen. Läkartidningen 1994;91:2864-2865.

15. Håkansson A, Pettersson Lindberg E, Henriksson K. Kurser i grundläggande forskningsmetodik till nytta för kliniker. Tolv års erfarenheter från Sydsverige. Läkartidningen 2002;99:1078-1083.

16. Hälso- och sjukvårdslagen, 26§. SFS 1982:763.

17. Anderberg & Forsell, 2011. Private paper.

18. Mosshammer D, Roos MJ, Kronenthaler A, Lorenz G, Eissler M, Joos S. Students´performing of practical research tasks for their scientific qualification – an approach within the family practice internship in undergraduare education. GMS Xeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung 2011:28(2);8-14.

19. Nilsson G, Josefsson A, Kiessling A, Sjöberg Bexelius T, Ponzer S. Nytt läkarprogram på KI. Professionen i fokus och forskningsprocessen som pedagogisk grund. Läkartidningen 2009;106:2847-2855.

20. Ilic D, Forbes K. Undergraduate medical student perceptions and use of Evidence Based Medicin: A qualitative study. BioMed Central Ltd. 2010;10:58. Doi:10.1186/1472-6920-10-58

21. Askling, B., Christiansson, U. & Foss-Fridlizius, R. (2001) Livslångt lärande som idé och praktik i högskolan. Rapport 2001:1 R. (Stockholm, Högskoleverket (the National Agency for Higher Education)).

22. Mark, E., (2009) Livslångt lärande ur bildningsperspektiv som strategi för högskolan Grundtviginstitutet vid Göteborgs universitet rapport nr 7

23. Ley TJ, Rosenberg LE. The physician-scientist career pipeline in 2005. Build it, and they will come. Jama, 2005:294(11);1343-1351.

24. She L, Wu B, Xu L, Wu J, Zhang P, Li E. Determinants of career aspirations of medical students in southern China. BMC Medical Education 2008:8;59 doi.10.1186/1472-6920-8-59

25. Kalaitzakis E. Attityder gentemot forskning bland läkarstuderande och ST-läkare: en enskätstudie. Downloaded 2011-12-07 http://www.sahlgrenska.gu.se/digitalAssets/127 5/1275787_kalatizakis_e.pdf

26. http://www.eucen.eu/about/aims_and_objectives

27. Viren N. Naik, MD • Anne K. Wong, MD, PhD Stanley J. Hamstra, PhD Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth (2012) 59:213–223 DOI 10.1007/s12630-011-9640-1

28. Irby, D (2011) Editorial. Medical Teacher Vol. 33 Issue 7, p547-550, 4p

29. A. Crellin Revalidation and Lifelong Learning Clinical Oncology Volume 23, Issue 10, December 2011, Pages 657–658